Big League Stew honors a birthday boy per week by taking a longer look at his career. Please join us in lighting the candles.

Big League Stew honors a birthday boy per week by taking a longer look at his career. Please join us in lighting the candles.

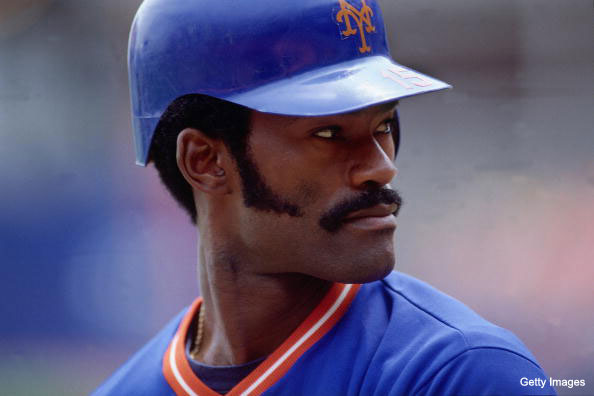

George Foster was one strong dude. He exploded for 52 homers in 1977 back when that actually meant something and was the only player between Willie Mays in 1965 and Cecil Fielder in 1990 to hit that mark. (For comparison's sake, there have been 24 seasons of 50 or more home runs between 1995 and 2011.)

Still, 1977 was somewhat out of character for Foster. He hit 52 in 1977, 40 in 1978, 30 in 1979, and fewer than 30 in every other season of his career.

After being drafted by the San Francisco Giants, who already had their corner outfield position occupied by Bobby Bonds, Foster was traded to the Cincinnati Reds. He'd spend the next 10 seasons as a key member of the Big Red Machine, batting a combined .326 in three World Series appearances. He then was traded to the Mets at the age of 33. They signed him to a five-year, $10 million contract, only to see him post the worst season of his career. This made him one of the charter members of the continually expanding list of Mets busts, as catalogued by The Captain's Blog, joined by Rusty Staub, Vince Coleman, Bobby Bonilla, Roberto Alomar, Kaz Matsui, Pedro Martinez, and Jason Bay. (Not to mention Mo Vaughn, who was also obtained by trade.)

His career basically ended in New York, too, during the bizarre 1986 season. He struggled for much of the year, but was still seen as one of the faces of the franchise, helping to put together the "Get Metsmerized" rap video for his team. Later in the summer, as Mookie Wilson was returning from injury, the team decided to keep Lenny Dykstra in center field rather than give Mookie his old job back. Foster criticized the team for that decision, and the team released him immediately. (He was batting .227 at the time.) Because Foster and Wilson are black and Dykstra is white, the issue of race inevitably came up. As Ira Berkow reported for the New York Times, manager Davey Johnson felt insulted by his comments, believing that Foster had implied that his decision was racially motivated. For his part, Foster believed that he had been misinterpreted, and stated that he believed neither the Mets organization nor Davey Johnson were racist.

The Chicago White Sox picked Foster up after the controversy, and he played 15 games for them, hitting .216/.259/.353, while his former team went on to win the World Series. Though he waited for a phone call for the next two years, no team ever decided to employ his services as a player again.

Best year: 1977: .320/.382/.631, 52 HRs, 149 RBIs, 6 SBs, 4 CS, 61/107 BB/K, 8.2 rWAR

After finishing as the MVP runnerup in 1976, George Foster was rightly perceived as one of the most dangerous hitters in the game. And he simply leveled the league in 1977. He may not have been the single-best player in the NL in 1977 — according to WAR analysis, that was Mike Schmidt, largely because of his incredible glove at third base — but Foster was certainly the most devastating hitter.

Foster may look even more impressive in contemporary eyes due to his staggering RBI totals. He led the league in 1976 with 121 RBIs, which helped him finish higher in the MVP voting than other players who had better seasons by WAR, including Schmidt, Garry Maddox, Pete Rose, Ron Cey, and Cesar Cedeno. When he posted 149 RBIs in 1977, it was the highest total since Tommy Davis in 1962, and no National Leaguer would clear that mark again until 1996, when Andres Galarraga did so with an assist from Coors Field. Of course, it isn't hard to drive in a ton of runs as a cleanup hitter when you have a leadoff hitter like Pete Rose and a No. 3 hitter like Joe Morgan to board the bases, but that doesn't take away from Foster's power surge. He had the highest home run total in the league for 25 years and the highest RBI total in the league for 45 years. Eye-popping.

Worst year: 1982: .247/.309/.367, 13 HRs, 70 RBIs, 1 SB, 1 CS, 50/123 BB/K, 0.5 rWAR

What in heaven's name went wrong? Up to this point in his career, Foster was a career .286/.355/.512 hitter who had finished third in the MVP voting in 1981, had finished in the top three during three of the previous six seasons, and had hit at least 20 homers in seven straight seasons. When he came into Shea Stadium as a visitor, he killed it. Going into 1982, he was a career .339/.358/.572 hitter in Queens, with 10 HRs and 43 RBIs in 48 games.

And then his career took a quick turn for the worse, from the moment he laced up his spikes as a Met. He hit .251/.306/.420 over the next five seasons of his career, with virtually identical numbers home and away. (Once he joined the Mets, he hit .250/.307/.429.) He slowed down, walked less, and got older in a hurry. In fairness, he was much better in 1983-1985 than in either 1982 or 1986, but "better" didn't mean he was good: at that point in his career, his mid- to late 30s, he combined a basically average bat and below-average defense. The Mets were likely looking for a reason to dump him and his contract for years, and when he obliged them by criticizing Johnson's decision on who to play in center field, they were only too happy to use it as an excuse.

Weird claim to fame: Get Metsmerized! George Foster was apparently the mastermind of "Get Metsmerized," and he was also the first MC to rap on the record:

I'm George Foster, I love this team

The Mets are better than the Red Machine

I live to play, and that's my thing

This year we're gonna win the Series ring.We play together, our team's real tight

Don't mess with us, we're dynamite

Strawman, Darryl, it's all the same

Call him Berry, what's in a name?

As Leslie Gilbert wrote in Advertising Age, the "Metsmerized" slogan was owned by Foster's merchandising company, and he was very savvy in cross-promotion. As the song's co-writer, Aaron Stoner, explained to Gilbert: "The record will promote sales of the Get Metsmerized merchandise that George Foster's company sells, and the familiar slogan will help sales of the record."

Unfortunately, they forgot to write a song that anyone in their right mind would want to listen to. As Bill Price of the New York Daily News wrote in 2006:

The record was so bad that later that season the Mets released a song called "Let's Go Mets," which is dubbed on the album cover as "The Official Record of the 1986 New York Mets."

Off the Field: "Get Metsmerized" wasn't the only example of Foster's merchandizing savvy. He was also the first person to realize the importance of Carlton Fisk's famous home run in 1975, before the current boom of historic baseball merchandise really hit its stride. He caught the ball off the foul pole in the 1975 World Series and took it home with him, as no one else asked for it. He then held on to it for 24 years, after Todd McFarlane considerably upped the price for historic home run balls by paying $3 million for the ball that Mark McGwire hit for his 70th home run. Foster got more than $113,000 for the ball that no one wanted.

Foster has always stayed active in baseball. He has spent a lot of time coaching in baseball camps and clinics. His latest clinic was just announced a couple of weeks ago: Feb. 11 and 12, in Batesville, Ind. Last year, he also worked as a United States-based scout for the Orix Buffaloes of Nippon Professional Baseball.